Canada’s Prayer Book

(A lecture given on November 1st, 2022 at St. Olave’s Church in Toronto, by Dr. Jesse Billett, associate professor in the Faculty of Divinity at Trinity College, Toronto.)

(A lecture given on November 1st, 2022 at St. Olave’s Church in Toronto, by Dr. Jesse Billett, associate professor in the Faculty of Divinity at Trinity College, Toronto.)

I have been tasked with speaking about Canada’s Prayer Book. And it’s a delight for me to do so, because this is a topic on which I teach at Trinity College – although I tend to take to take my students further back; I insist that they know England’s Prayer Book before they come to appreciate Canada’s. But I’m pleased tonight to think about the meaning and significance of the Canadian Book of Common Prayer, and to do so in the 60th year since it was formally adopted by General Synod in 1962.

I want to divide my remarks into four sections. First, I want to talk about the Book of Common Prayer as the embodiment of the mind of the Church. Second, I want to investigate the question of whether there can be local Prayer Books at all, if the Prayer Book represents the mind of the whole Church. Third, I want to talk about the history of revision of the Prayer Book in Canada; in particular, the challenge that was faced in reconciling “high-church” Anglicans with “low-church” Anglicans. And then in conclusion, I want to talk about the achievement of the most recent Canadian Prayer Book in terms of a contrast between consensus and compromise, as a way of evaluating our current liturgical moment and also things that have unfolded in the decades since the 1962 Canadian Prayer Book was adopted.

So let’s turn first to the Prayer Book as “mind of the Church”. I quite like a summary that was offered by the great church historian, Owen Chadwick, about what Archbishop Cranmer achieved in the original Book of Common Prayer. He said, “The diverse elements upon which [Cranmer] worked, traditional or Protestant, were taken up by his careful scholarship and transmuted into a beauty, at once delicate and austere, of liturgical prose and poetry. Liturgies are not made, they grow in the devotion of centuries; but as far as a liturgy could ever be the work of a single mind, the Prayer Book flowed from a scholar with a sure instinct for a people’s worship.” (The Reformation, 2nd rev. repr., Pelican History of the Church 3, London, Penguin Books, 1972, p. 119.) And so, although a liturgy must necessarily grow organically if it is to have an authenticity, Chadwick says, I think rightly, that Archbishop Cranmer accelerated the process for the Church of England’s liturgy in English at the time of the Reformation, with a new evangelization of the people of England.

And I think it’s important to realize that there was fundamental continuity between what had gone before and what the Prayer Book brought into being. Liturgical scholars sometimes argue over what Cranmer really thought about the finer points of Reformation doctrine, Protestant versus traditional Catholic. But really, I think what Archbishop Cranmer personally thought is largely irrelevant; because the working procedure that he adopted in crafting the Prayer Book was such as largely to exclude his own opinions. “We’re going to look at the tradition of the Church”, he said in effect. “And whatever we can keep of the tradition of the Church, that has not been unfortunately radically misunderstood by our people, we will keep. But the words that we use to talk about that tradition, or to offer our prayers in our traditional rites, will necessarily either be drawn from Scripture, or paraphrased, or compatible with Scripture.”

And so when we look at the prayers that Cranmer himself composed, it’s astonishing to discover that what he did was to go largely through the New Testament, find every passage he could that was relevant to the part of the liturgy in question, and stitch them together into prayers following the traditional pattern but using only Scriptural language and imagery. If you ever take a concondance of the Bible and work your way through the Prayer Book, you’ll be amazed by this. I think the most famous example is the General Confession at the beginning of Morning and Evening Prayer. One scholar examined it and identified nineteen different biblical quotations and allusions that had been merged together to make that one prayer. (In fact, I’ve found more!) It is still the tradition of the Church, but it is now being expressed in that scriptural language.

There ’s a wonderful Anglican thinker and writer who died eleven years ago, Father Robert Crouse – I’m sure many of you have heard of him. This is what he had to say about Archbishop Cranmer’s methods: “The clear word of Holy Scripture was to be the criterion; and within that criterion, the Reformers strove for continuity and comprehensiveness. The continuity they sought and effectively maintained was a continuity with the developed and living tradition of their own Church; that is to say, the tradition of Latin Christendom as it existed in the English Church. But within that context, they drew inspiration from a wide variety of sources: contemporary continental, Roman Catholic and Protestant, as well as ancient and Eastern liturgies, of which they had a remarkably precise knowledge. Beyond the most essential points, the liturgy they provided was not a very precise theological document, but rather broad, flexible and comprehensive. The value of those qualities in the Prayer Book has been abundantly demonstrated in subsequent centuries of Anglican history.”

Father Crouse says elsewhere – and this is where I really want to come to the point about the mind of the Church – “We must not expect to find in the Universal Church any very specific human locus of authority. What we must look for, rather, is the Church’s common mind, what is technically referred to as the Consensus Fidelium, the common mind of the faithful in relation to the Word of God revealed. It was the Church’s common mind which, over a period of several centuries and not without dispute, established the Canon of Holy Scripture. It was the Church’s common mind which promulgated credal affirmations and conciliar formulations. It was the Church’s common mind which defined the Church’s position on the forms of apostolic ministry and sacramental practice and established the norms of moral and ascetical life. By common mind, Consensus Fidelium, we do not mean current popular Christian opinion. It is not a matter of counting heads or taking plebiscites. Truth is not established that way. You know, if you had tried that method, say, in the middle of the fourth century, the result would probably have been Arianism [that great heresy so valiantly combatted by St. Augustine]. If you had tried it in any later century the result would almost certainly been a kind of unwitting Pelagianism. No, the Consensus Fidelium is the mind formed (and by no means always popularly) by the Church’s ongoing, serious, and devout attention to and submission to the Word of God, unconformed to the wisdom of this present age. It is then expressed with greater or lesser precision and in varying degrees of authority in credal and conciliar pronouncements, in liturgies, canon law, and in the theological tradition as a whole. What we are speaking of, then, is the living, developing tradition of the universal Church, as it is guided by the Spirit in relation to the revealed Word of God. Now that traditional consensus is really the only fundamental authority in the Church of God.” (From “The Prayer Book and the Authority of Tradition” in Church Polity and Authority, ed. G. Richmond Bridge, Charlottetown, St. Peter Publications, 1985, pp. 53–61.)

And he goes on to say, “The Book of Common Prayer is the form of the collective memory of Anglicans – the Consensus Fidelium (the common mind of the Church), the principle of authority and cohesion of the institution, and the guarantee of its catholicity. Authority for Christians is fundamentally the authority of the Word of God, expressed in holy Scripture. Anglicanism, in particular, is a certain way of hearing and understanding and living by the Word – an ongoing exegesis [explanation] of God’s Word, fostered by and expressed in the tradition of common prayer. In no other church in Christendom does liturgy play so crucial a role. Anglicans recognize no papal magisterium; for us it is the tradition of common prayer which elucidates and defends and deepens our memory of the Word of God. The destruction, or neglect, of that tradition induces a crippling amnesia.” (“The Form of Sound Words – the Catholicity of the Prayer Book”, posted on the PBSC website: prayerbook.ca/the-form-of-sound-words.) If we lose that tradition, he is saying, we lose our collective memory. And the Prayer Book, as developed and passed down through the centuries, is our collective memory, our agreed position, the common mind of the Church.

There was another writer of the Church of England, Martin Thornton, who said that the original reformed Church of England didn’t need a Pope because it had the Prayer Book, and people living by its pattern were able to work out answers to the theological questions that presented themselves in their own day. By contrast, Fr. Thornton says, “The modern Church has to face such questions as nuclear armament – or disarmament – birth-control, gambling, industrial relations, and so on, and it is justifiably accused either of saying nothing about them or of speaking with a divided voice. Two bold bishops will make honest, sincere, forthright, and contradictory pronouncements about any of these things, but this is not the opinion of the Church, nor even the Church giving a lead. It is but the view of a Christian individual against which the decisions argued out in the Reverend Mr. Baxter’s house on Thursday evenings [that is, the “open houses” held by the Puritan Richard Baxter in his home to discuss the previous Sunday’s sermon] carry far more moral authority. For that was at least the microcosmic Church, comprised of individuals grounded in the Rule of the Church, living daily within the channel of grace. Do all members of the average Diocesan Conference, or of the House of Laity, live seriously and loyally by the Prayer Book pattern? Unless, or until they do, those bodies are theologically incapable of making decisions of any real weight. In the seventeenth century, individual liberty of conscience was firmly guarded, yet the ‘opinion of the Church’ had real meaning. To-day it has not; not because individual Christians lack integrity or courage, but because they are not acting as, are not being, the Church.” (English Spirituality: An Outline of Ascetical Theology according to the English Pastoral Tradition, London: SPCK, 1963, pp. 238–39.) Thus, doctrine is not arrived at by a vote. Doctrine is arrived at by the ongoing memory of the proclamation of the apostles, enshrined in holy Scripture, as lived in the Church century after century. And that is what the Book of Common Prayer passes to us, as Anglicans.

So if that’s the case, I want to move on to my second topic and ask, can you actually have a local Prayer Book at all? Because if there is one deposit of faith, one agreement among at least Anglicans about the contents of that faith, can the Prayer Book be different in different places? We are used to the idea of a Canadian Prayer Book, an American Prayer Book, a Scottish Prayer Book, an Australian Prayer Book, a South African Prayer Book, a Prayer Book of the Church of South India, a Prayer Book of the Japanese Anglican Church, and so on. But perhaps we should stop to consider how that came to be, and indeed whether it ought to be. From the beginning of international Anglicanism this was a concern. Now of course the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States had found it necessary to have a revised Book of Common Prayer at the time of the American Revolution; because the 1662 Prayer Book contained a lot of references to the sovereign of England. English bishops and other clergy had to swear an oath of loyalty to the Crown, and that could not happen in the new republic of the United States of America. And so a new Prayer Book was created on that occasion. That was the only one for a long, long time. Many of you may have heard about the failed Scottish Prayer Book of 1636-37. I think that only goes to prove my point – there was an attempt to give Scotland its own Prayer Book, and the result was a civil war – Presbyterians marching down and conquering England! It wasn’t a pattern that recommended itself to future ages!

At the very first Lambeth Conference – the gathering of the bishops from the whole Anglican world, in 1867 – this was on their minds. One of the resolutions passed said, “That, in order to the binding of the Churches of our colonial empire and the missionary Churches beyond them in the closest union with the Mother-Church, it is necessary that they receive and maintain without alteration the standards of faith and doctrine as now in use in that Church” – those standards being the 1662 Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England, the 39 Articles of Religion, and the canons ecclesiastical of 1604. Just over ten years later, at the second Lambeth conference of 1878, a committee report recommended: “Your Committee, believing that, next to oneness in ‘the faith once delivered to the saints’, communion in worship is the link which most firmly binds together bodies of Christian men, and remembering that the Book of Common Prayer, retained as it is, with some modifications, by all our Churches, has been one principal bond of union among them, desire to call attention to the fact that such communion in worship may be endangered by excessive diversities of ritual.” The background to that was the “Ritualism scare” in the Church of England, which was also “infecting” other parts of the Anglican Communion. Priests were using candles on the altar – and calling it an altar! They were wearing vestments! It was shocking. In 1874 there was actually a Public Worship Regulation Act passed in the Church of England, under which certain priests ended up being jailed. Now, that so revolted the popular conscience that they had to back down. But the idea of a rising Anglo-Catholicism was very much on the minds of the bishops at Lambeth in 1878, who said that we must not just have one text, but we must have boundaries as to how we use it. Ten years later, in 1888, this resolution was passed at the third Lambeth Conference: “That, inasmuch as the Book of Common Prayer is not the possession of one diocese or province, but of all, and that a revision in one portion of the Anglican Communion must therefore be extensively felt, this Conference is of the opinion that no particular portion of the Church should undertake revision without seriously considering the possible effect of such action on other branches of the Church.” In other words, the Anglican mind in the 1860s, 70s and 80s seemed to be very much against local revisions of the Book of Common Prayer. So now you see the background of my question, whether there can be local versions of the Consensus Fidelium, of the mind of the Church.

Now we finally arrive in Canada. The first General Synod of the Church of England in the Dominion of Canada, as it was then called, met in 1893 at Trinity College. And there they made a Solemn Declaration, which you will still find printed near the front of our Book of Common Prayer, which included the following: “We are determined by the help of God to hold and maintain the Doctrine, Sacraments, and Discipline of Christ as the Lord hath commanded in his Holy Word, and as the Church of England hath received and set forth the same in ‘The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, according to the use of the Church of England; together with the Psalter or Psalms of David, pointed as they are to be sung or said in Churches; and the Form and Manner of Making, Ordaining, and Consecrating of Bishops, Priests, and Deacons’; and in the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion; and to transmit the same unimpaired to our posterity”. The Lambeth Conference bishops would have rejoiced at such a statement, because a large section of what I’ve just read out is actually the long title page of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, which was the Prayer Book as used in Canada right up until the time of that first meeting of the General Synod in 1893.

The trouble is, though, that liturgies don’t really work that way. You can’t just let them sit unaltered, because the world in which Christians live continues to change, the challenges that face us change, and some very basic things change, like what is possible, or appropriate to do in certain circumstances, that the framers thereof could not imagined. And this is why I’m again going to quote Father Crouse. He says this about Prayer Book revision: “Tradition is, and must be, open to growth. Liturgies have been, and must be, revised from time to time.” And that was the situation that quickly faced Canadian Anglicans already in the 1890s, because of the different conditions in this new land. For example, in England it was extremely rare for a new church ever to be built, at least up to the 19th century; and so the Book of Common Prayer provided no liturgy for consecrating a new church building. And there was no liturgy for hallowing of a new cemetery. So, Synod authorized forms of liturgy that could be used for these purposes. And over time there accumulated many such pamphlets and booklets that bishops and clergy had to keep track of, with a fair bit of uncertainty as to what to use on any particular occasion. So the challenge was, how do we adapt the tradition that we have received to this land, where the local needs are different from what they were in the place in which we received the mind of the Church? And the great complication was that this coincided with that anxiety to which I referred a little earlier – the emergence of the high churchmen, the Anglo-Catholics, countered by the low-church staunch defenders of evangelical Protestant orthodoxy trying to resist them as much as they could.

The beginning of the Anglo-Catholic movement is usually dated to 1833, when John Keble preached at Oxford his famous sermon against national apostasy. But actually, I think you can probably back-date it to the year 1827, which is when a young professor in Oxford called Charles Lloyd offered a series of lectures on theological subjects, including the Prayer Book, to a select invited audience. Among them were the two great lights of what was later to be known as the Oxford Movement, the Catholic revival in the Church of England: John Henry Newman and Edward Bouverie Pusey. The very simple point that Lloyd impressed on his hearers was that most of the texts in the Book of Common Prayer were not composed at the time of the English Reformation, but were translations into English of very ancient Latin liturgical texts that the Church of England held in common with the Church of Rome. This was an essential insight for the Catholic revival: the Prayer Book showed that the Church of England was not a creation of Parliament in the 16th century, but the continuing presence of the Church Catholic in England that had been founded in 597 by Pope Gregory I and St. Augustine of Canterbury. That insight led to a great spiritual awakening in the English Church. But it was not welcomed everywhere; some people argued that if the Prayer Book was Catholic, then it had better be revised to be more Protestant!

Later in the nineteenth century, though, the discovery that the Prayer Book was “Catholic” was counterbalanced by the discovery that it was also profoundly “Protestant”. We should not be surprised that it was Roman Catholic scholars who pointed this out. I have on my bookshelf a copy of Edward VI and the Book of Common Prayer by Cardinal Gasquet and that prince of liturgical historians, Edmund Bishop (first published in 1890). This work points out in the bluntest possible way that the Book of Common Prayer was a radical departure from the medieval Catholic liturgy, and that it embodied a revolutionary Protestant theology. It was only a few years later that Pope Leo XIII declared that Anglican orders were “absolutely null and utterly void”, implying that the Church founded by St. Augustine of Canterbury had ceased to exist at the time of the Reformation. Well, that announcement was welcomed with joy by the low-church evangelical wing of Anglicanism. And the person who previously owned my copy of Gasquet and Bishop’s book filled it up with underlining and enthusiastic marginal notes expressing delight at finding that it proven that the Prayer Book was a rejection of all things Catholic. That reader was one Dyson Hague, who was from 1912 professor of liturgics and ecclesiology at Wycliffe College. It would be fair to say that to this day Hoskin Avenue marks a dividing line in the history of the interpretation of the Book of Common Prayer, with the low-church evangelicals at Wycliffe College on the south side of the street, and the high-church Anglo-Catholics at Trinity College on the north side. Although I am happy to say that overt hostilities ceased long ago, and in fact now the mandatory course on Anglican liturgy for students enrolled in the M.Div. program at both Wycliffe College and Trinity College is taught jointly by myself and the principal of Wycliffe College, Bishop Stephen Andrews. And so we have found a consensus in our teaching of liturgy.

So one of the challenges in producing a revision of the Prayer Book for use in Canada was to reconcile these opposing views. And there was in fact strong resistance to the idea of revision. In the late 19th century, the idea was proposed that we should keep the 1662 Prayer Book as it was and just add an appendix of all the extra things that were felt to be needed for Canada. Some of the things that were included in the proposed appendix were an order for the making of a deaconess; the institution and induction of a minister into a new cure; the laying of the foundation stone of a church; a service for the acceptance of baptismal vows; the solemnization of marriage in an unconsecrated building; confirmation celebrated immediately after adult baptism; the burial of a baptized infant; the hallowing of a grave in unconsecrated ground; forms of prayer for the visitation of prisoners. Well, a draft was presented to General Synod in 1905 and it was 260 pages long – quite an appendix! And the historian of the eventual revision of the Canadian Prayer Book in 1918-1922, W.J. Armitage, said this: “It had a short shrift, for it had many enemies who stood ready to kill it and bury it beyond recall. When Dr. Dyson Hague was asked to summon from the shadowy past that memorable scene in old Quebec [when Hague spoke against the Appendix], he wrote: “The main thing that I remember is that as I passed down the stairs you stopped me and said, ‘Hague, you knocked it stiff!’” (W. J. Armitage, The Story of the Canadian Revision of the Prayer Book , Cambridge University Press, 1922, p. 11.) Hague had given a speech at the General Synod and after that it was voted right down. Although I do think one interesting proposal of that attempted revision was this: to have an edition of the Prayer Book available in different sizes, but with the page numbers identical. That had actually never existed in the past. That is, the priest at the reading desk could not say, “Turn to page x” – you just had to know the liturgy inside out, because every different edition had its own particular pagination – something we don’t realize nowadays.

So the decision was ultimately made that we would not have an appendix, but we would actually revise our whole Prayer Book; and a committee was duly struck in 1912. It was chaired by the Bishop of Huron, David Williams, and the secretary to the revision subcommittee was W.J. Armitage, the archdeacon of Halifax, whom I’ve just quoted. And the Anglo-Catholic versus evangelical mutual suspicion presented itself almost immediately, because the evangelicals on the revision committee proposed a motion that said that this committee must not approve any changes that would involve a change of doctrine, or would even imply a change of doctrine. So that was a hurdle that had to be got over, and this was done by simply deciding not to touch certain things. The service of Holy Communion, for example, was left almost completely unrevised in the eventual book of 1922. And that bequeathed a legacy of further strife for the Canadian church, because that was the most argued-over liturgy in Anglicanism. So there were clergy who were going in every kind of direction, tinkering with different options such as the English Missal or the Anglican Missal – taking the rite of the Prayer Book, rearranging it to make it look a little bit more medieval, adding all sorts of extra text – and it was just liturgical chaos over the following years.

Nevertheless, there were some really interesting changes made in the 1922 book. I think that the most interesting ones are perhaps in the burial service. For example, there’s a recognition that over large areas of Canada the ground freezes in the winter. And so if a person dies in such areas in the dead of winter, the funeral service and the interment of the corpse may have to be separated in time. So a rubric was inserted saying that at the minister’s discretion, the service could conclude with the Lesser Litany and the Lord’s Prayer, and then the service would be resumed when it became possible to dig a grave. It also introduced special options for the burial of children, which had never been provided previously. The 1662 Prayer Book does not differentiate between the burial of a child who has died shortly after birth and the burial of someone who has lived to a ripe old age. But the mode of mourning is different on those two occasions, and this Prayer Book revision acknowledged that and provided for it. Another, subtle change was made to the rubric at the beginning of the burial service, which in the 1662 book said that this office was not to be used for “those who have laid violent hands on themselves” – that is, that suicides must not be given Christian burial in this form. The 1922 book altered the wording to “those who have died by their own wilful act”; i.e. if you were deranged and didn’t actually wish to kill yourself, then you would be permitted to receive this Christian burial; acknowledging the existence of psychological situations which we perhaps understand a little bit better nowadays.

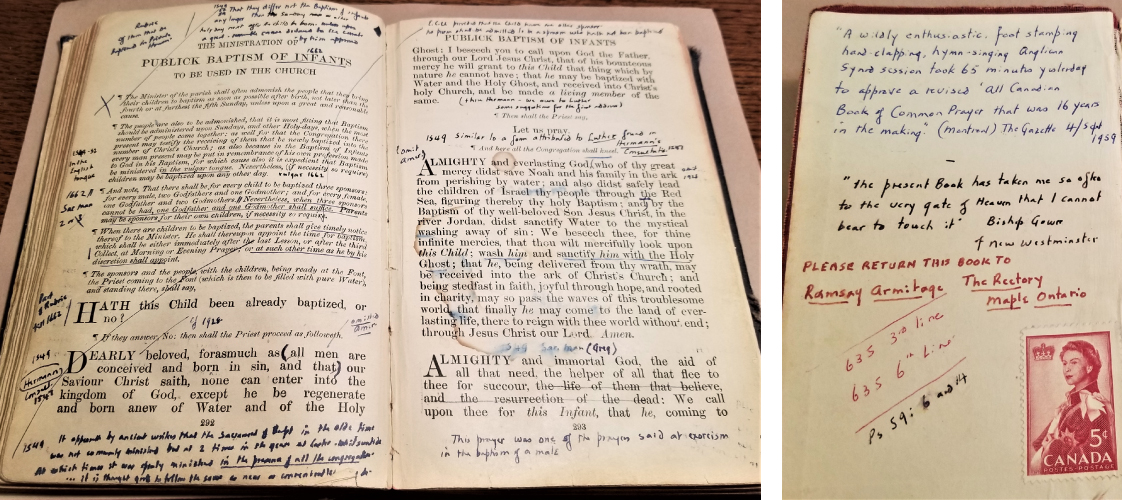

So that book went out; and within twenty years it was decided that we needed to have another go. In 1943, on September 14th, a new revision committee met at St. Hilda’s College, right next door to Trinity College. This revision took quite a long time. We have, in the Trinity College rare books collection, several copies of the Book of Common Prayer that were filled with annotations by a prominent member of the revision committee – the principal of Wycliffe College, Ramsay Armitage. He noted how long it took to produce our revised book compared with those in other countries – Scotland, Ireland, the United States – and ours took the longest time: sixteen years, from 1943 to 1959. So, a lot of work by this committee! The principles of their revision were quite straightforward, and they are laid out in the preface to the 1959-1962 book: “The aim throughout has been to set forth an order which the people may use with understanding and which is agreeable with Holy Scripture and with the usage of the primitive Church. And always there has been the understanding that no alterations should be made which would involve or imply any change of doctrine of the Church as set forth in the [1662] Book of Common Prayer.” So the revision process was committed to maintaining the principle of no doctrinal change. But how was that to be attained, given the ongoing tension between high and low? I’ve already mentioned that one of the members of the revision committee was Principal Ramsay Armitage of Wycliffe College, representing the evangelicals. To counterbalance his voice on the committee a Trinity man was selected, Father Roland Palmer of the Society of St. John the Evangelist, which had its headquarters in Bracebridge, Ontario. At the first meeting, Principal Armitage arrived early, and when Father Palmer came in, he said to him, “Father Palmer, come sit by me where I can keep my eye on you!” And at every meeting of that committee, they always sat together; and what’s more, before every meeting, the two of them would get together and discuss the options that had been proposed, and talk about what would be desirable or problematic for Anglo-Catholics or for evangelicals. And they would work out an agreement that was satisfactory to both of them, and then they would bring that to the committee, so that evangelicals and Anglo-Catholics were able to speak with one voice.

What are the characteristics of that 1959 book? I find it remarkable to study. It hews very closely to the 1662 book, but with astute awareness of every other contemporary option in the Anglican world. Those annotated books that Principal Armitage has left are colour-coded with marginal notes, indicating the origin of every separate revision and the reason for it. He also records Father Palmer’s overall description of the revision work: “In our work of revision there was no conscious copying of this or that rite, but a setting forth of … ‘an order agreeable with Holy Scripture and the usage of the Primitive Church’ [an] order which must before all else be one ‘that the people can use with understanding’.” This aim of clarity is reflected in many places, but I’ll give just one example. In the service for the public baptism of infants, in the 1662 and 1922 books, the service had begun with this introduction: “Dearly beloved, forasmuch as all men are conceived and born in sin …”. Now, that’s just a direct quote from Psalm 51. But it was misunderstood by some people who thought it was saying that the very act of conceiving a child was sinful; which is not the teaching of the Church. And so in the 1959-62 book this was reworded as follows: “Dearly beloved in Christ, seeing that God willeth all men to be saved from the fault and corruption of the nature which they inherit, as well as from actual sins which they commit …”. So it unpacks that scriptural quotation and explains what it means – not changing doctrine one bit, but making it more “understanded of the people”.

I could go on with many other little examples of this kind, but I want to wrap up now with my fourth topic, which is consensus versus compromise. At the General Synod at which the Canadian Prayer Book revised draft was presented in 1959, the report was read by Archbishop Carrington in his role as chairman, and then according to a pre-arranged plan, the motion to accept the new Prayer Book was presented by a graduate of Trinity College and seconded by a graduate of Wycliffe College – representing acceptance of the book by both “high” and “low” Anglicans. There followed a standing ovation lasting many minutes, concluding with the spontaneous singing of the Doxology, “Praise God from whom all blessings flow”. The Montreal Gazette reported (as recorded in Principal Armitage’s notes), “A wildly enthusiastic, foot stamping, hand-clapping, hymn-singing Anglican Synod session took 65 minutes yesterday to approve a revised all-Canadian Book of Common Prayer that was 16 years in the making”. When the book came up for review again in 1962, one of the bishops, Bishop Gower of New Westminster (again, recorded in Principal Armitage’s notes) spoke firmly against any changes to it, saying “The present book has taken me so often to the very gate of heaven that I cannot bear to touch it.” Father Palmer subsequently wrote a wonderful commentary on the new book, called His Worthy Praise, and the person who contributed the foreword to the book was Principal Armitage. He wrote, “With most of His Worthy Praise I find myself in full, complete accord. Here and there I might say it differently, although everywhere I wish that I had the grace and competence to say it as well. And when I meet some statement which through inheritance and conviction I would challenge, I recognize that here we stand on that solid Anglican ground of true comprehensiveness which was a mark of the wide-embracing Christian Church in the New Testament and apostolic times.” In other words, you find the high churchman and the low churchman united; they may have their theological differences, but they can both use this shared liturgy in good conscience. We can all pray together because this is our consensus, our common mind.

Well, as we know, before many years had passed, there were already restless pleas for change: we must have contemporary liturgies, we must have updated language, we must have more options, we must have greater flexibility, we must be more informed by contemporary liturgical science and the discoveries of researchers. That led, of course, to all the trial liturgies of the 1970s and early 80s, and eventually to our Book of Alternative Services. My question is, how much consensus does our way of worshipping today reflect? We had this marvellous consensus greeted with spontaneous applause when our Prayer Book was adopted; now, I suggest, what we have is not consensus but compromise – that is, options are provided to satisfy the liturgical preferences and theological convictions of parties that disagree with each other. “I couldn’t use that liturgy in good conscience, but you can use it as long as I get to use this other one that you dislike.” To illustrate my point: in 1995, the evaluation commission on the Book of Alternative Services, looking at ten years of use of that book, delivered a report to General Synod, resulting in the passing of this resolution: “This Synod agrees to instruct the Faith, Worship and Ministry Committee to prepare as soon as possible supplementary material to the Book of Alternative Services containing a contemporary language eucharistic rite that embodies reformed theological conscience over such issues as the manner of the presence of Christ’s saving work on the cross, eucharistic oblation, and epiclesis [the invocation of the Spirit in the eucharistic prayer].” That resulted in a little gray booklet of supplementary eucharistic prayers and other services, that was published a few years later. And so the Book of Alternative Services now has its own book of alternatives to the alternative services, to address a sincere problem of theological conscience in a not inconsiderable portion of the church. That, I suggest, is compromise. And so now our liturgies reflect not a common mind, but a large variety of theological opinions.

And that’s where I think we are immensely fortunate in what has happened in the Canadian church, which is that we have preserved the Book of Common Prayer, which is, granted, in minority use – although I think making a comeback in many places! – as the official doctrinal and liturgical standard of the church. Because it says, here is our common mind. We’re working our way towards an update of our common mind, but we’re certainly not there yet. Therefore, we must preserve this, as the touchstone, as the point of common reference. And part of my mission at Trinity College is to draw our students’ attention to that. I’m going to conclude with another quotation, a final quotation from Robert Crouse, about the difficulty of consensus in theology and worship, especially since we do not have an authority that can tell us the answers. This is what he says: “The authority of consensus is not easy to live with. It involves learning and deliberation, debate and controversy, when we would prefer, perhaps, the peace of easy compromise. It involves the patience which must sometimes think in terms of centuries instead of months or years. It involves reverent, careful, and humble attention to the past when we are, perhaps, inclined to be preoccupied with the latest findings of biblical criticism or the social sciences or with the latest popular causes. And in the divided state of Christendom, the divided state even of our own communion, it involves, or should involve, the frustration and self discipline of refraining from local decisions which are not clearly justified by the Consensus Fidelium as more universally conceived in time and space.” (Robert D. Crouse, “The Prayer Book and the Authority of Tradition,” in Church Polity and Authority, ed. G. Richmond Bridge (Charlottetown: St. Peter Publications, 1985), pp. 53– 61.) It’s within that continuing, growing, developing Consensus Fidelium that I see the meaning and significance of our Canadian Prayer Book.

Below are samples of pages from Principal Armitage’s annotated Prayer Books.